In that distant summer of 1985, I landed in Puerto Deseado, a quaint city on the northern coast of Santa Cruz, the Jurassic Park in Southern Patagonia, with the aim of starting my doctoral thesis, through a research initiation scholarship granted by CONICET.

By Dr. Patricia Sruoga

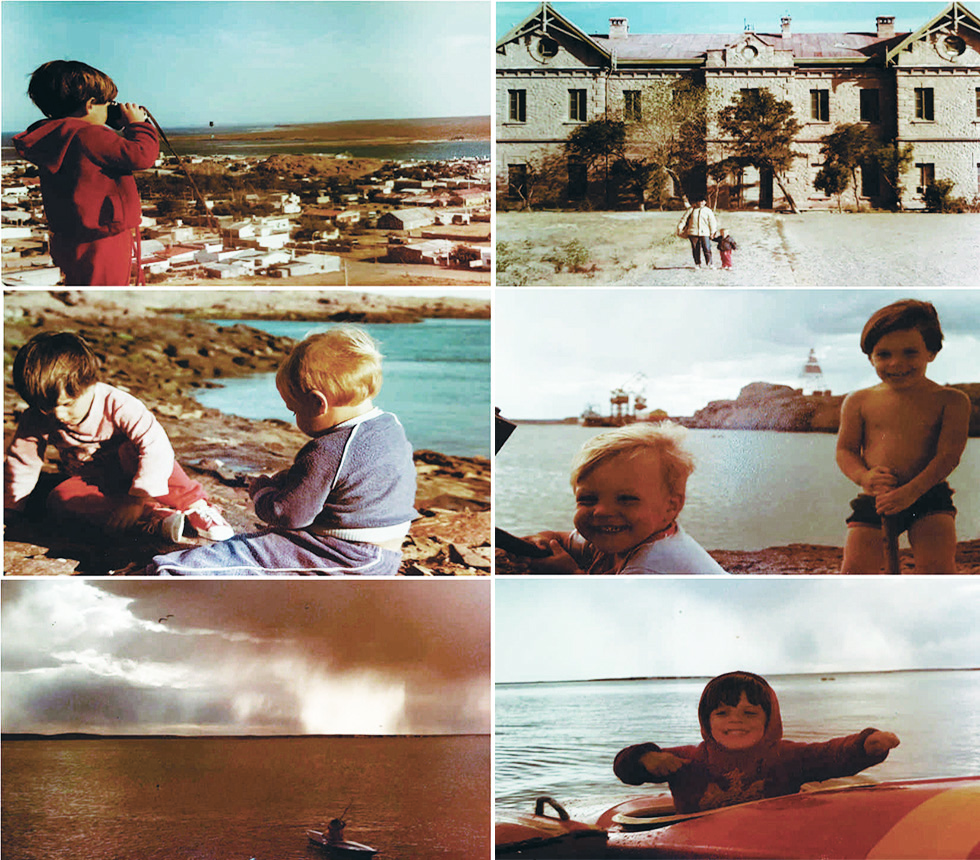

I fell in love at first sight with that city perched on reddish cliffs and overlooking a bittersweet inlet that connects the Deseado River with the Atlantic Ocean. Fragments of experiences still resonate in my memory, such as those languid sunsets mirrored in the inlet, moonlit kayaking excursions, my children Tomy and Gaby playing at being explorers, and the treacherous tide stealing my Topper sneakers…

I couldn’t have been happier: I was in the best place in Patagonia to collect samples for my thesis, in the company of my children! Indeed, the city is nestled in a rocky massif, whose age dates back to ~168 million years, that is, to the Jurassic period. The volcanic origin lands have a wide area distribution in Southern Patagonia. Rocks equivalent to those that contour the inlet are found throughout the province of Santa Cruz, both on the surface and underground, along the Southern Patagonian Andes and Tierra del Fuego, extending toward Antarctica and the continental shelf, covering a total area of ~1,000,000 km². The purpose of my research was to try to elucidate the type of volcanism that occurred during a crucial geological moment for the evolution of the supercontinent Gondwana, specifically just before its dismemberment and the consequent opening of the Atlantic Ocean.

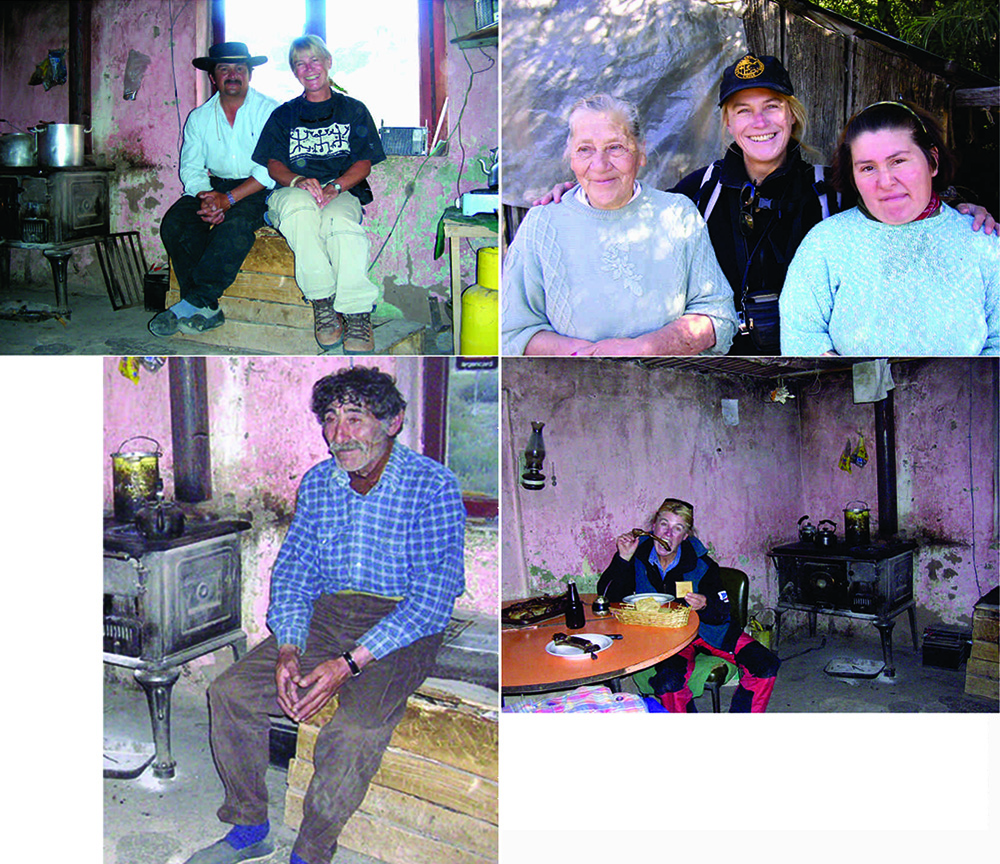

With pick in hand and filled with enthusiasm, I set out each day to explore the rocky outcrops, whether in the square or next to the supermarket, in the nearby ranches, on islets or cliffs populated with elegant cormorants, seagulls, frigates, and other diverse birdlife. Several summer campaigns followed in northern Santa Cruz, aiming to fulfill the thesis objective. As the mapping and sampling work progressed, I had the enormous privilege of getting to know the local inhabitants, befriending the ranchers, and enjoying their company and hospitality. I listened to many stories of solitude and abandonment by the warmth of the wood stove, while the endless round of bitter mate delayed our return and led to a dinner of capon with fried cakes. In those forgotten places on the maps, far from tourist circuits, where horizons stretch into vast uninhabited plateaus, I could weigh the value of human companionship. I never felt that veiled gratitude for the prolonged conversation sheltered from the wind again…

On one occasion, during an exploratory trip to Lake Posadas with colleagues from the British Antarctic Survey, one of them asked, “Are we still in Jurassic Park?” referring to the Jurassic age volcanic rocks, and I replied, “Yes, we are!” emphasizing the vastness and geological rarity of these ancient volcanic terrains, albeit without threatening Tyrannosaurus like in the film saga. From then on, I felt like a detective of that prehistoric world and began to try to decipher the paleoenvironment from the evidence provided by the rocks. I learned to interrogate and unveil the secrets of ignimbrites, which are the rocks that characterize this volcanism, leaving a peculiar mark not only due to their abundance but also because of their genetic significance.

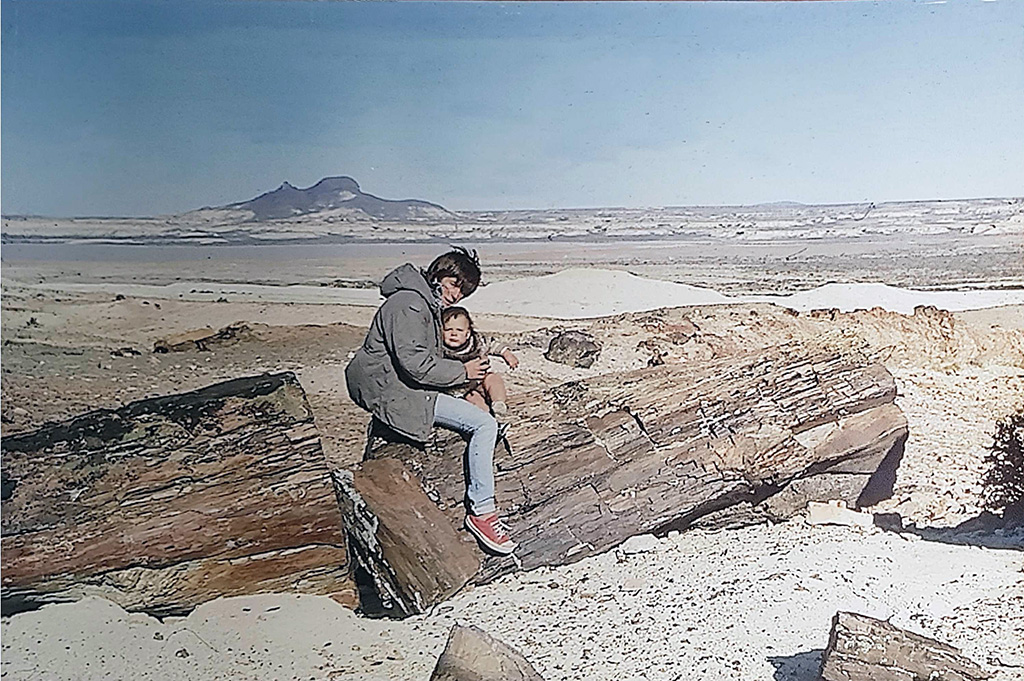

The Jurassic was a harsh period for the flora and fauna that inhabited this part of Patagonia. Indeed, it is estimated that for about 50 million years, this sector of the Gondwana supercontinent was akin to hell, where periodic explosive mega-eruptions generated incandescent clouds with devastating effects. Evidence of this includes the silicified trunks and cones of Araucaria that lie a rather unnatural death in the petrified forests discovered in Santa Cruz. These fossil remains, with excellent preservation, document very favorable climatic conditions for the development of fern and Araucaria forests that reached ~50 m in height. The relentless ignimbrite eruptions sealed a lush fate; many specimens died standing, and others lie in mute magnificence in the Natural Monument Petrified Forest of Jaramillo, located about ~200 km east of the city of Puerto Deseado.

If in the effort to compare the Jurassic Park in Southern Patagonia, we seek similar scenarios in historical times, indeed, no such extraordinarily vast eruptive events have occurred again on the planet, with such prolonged recurrence in time and devastating environmental impact. The fiery clouds that buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum (Italy) in 79 A.D., the catastrophic eruption of Santorini (Greece) that buried Atlantis in the Bronze Age, or the lateral explosion of Mt. St. Helens (USA) in 1981 that devastated the surrounding forests, pale in comparison to the colossal fiery violence of those remote eruptions.

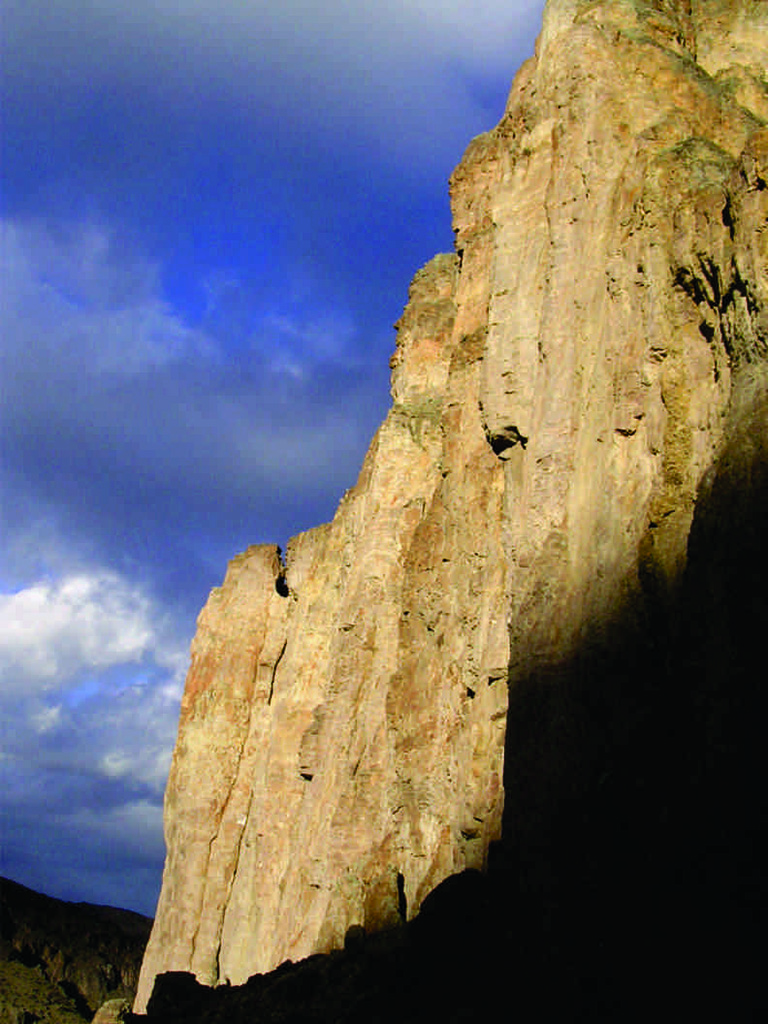

The passage of time and its fierce erosions carved the rocky massifs into unique sculptures and excavated caves and overhangs that served as shelter for the first inhabitants of the area against the harsh climatic conditions. In these coveted refuges, those ancient hunters left us a valuable legacy of rock art. Undoubtedly, the most famous site is the Cave of Hands, in the Pinturas River, where hand paintings and hunting scenes abound. Archaeologists have discovered that the cave has been periodically occupied between ~10,000 and ~700 years ago by the ancestors of the Tehuelches. This has been documented on the cave walls by the superposition of types and styles of pictographs and the use of certain pigments. Could it be that the long winter stays in the caves sparked artistic inspiration?

In contrast, Charles Darwin’s impression upon approaching the Deseado canyon during his voyage aboard the Beagle in 1833 was rather desolate, as revealed by his own words (“I do not believe I have ever seen a place more isolated from the rest of the world than this rocky crevice in the middle of such an extensive plain,” referring to the place now known as the Darwin Lookouts).

In more recent times, the Jurassic rocks attracted business interest due to their economic importance, either as a reservoir of oil and gas or for their gold and silver mineralization. I had the opportunity to provide advice to assess their potential from a perspective distant from the strictly academic, bridging the gap between scientific research and industry.

The Jurassic Park of Southern Patagonia is a portal to wonder, both for scientists and lovers of natural treasures. Geologists, paleontologists, and archaeologists continue to explore and discover remnants of climates, environments, and extinct beings. Tourist attractions such as the Natural Monument Petrified Forest of Jaramillo or the Cave of Hands are just some of the most well-known and internationally relevant.

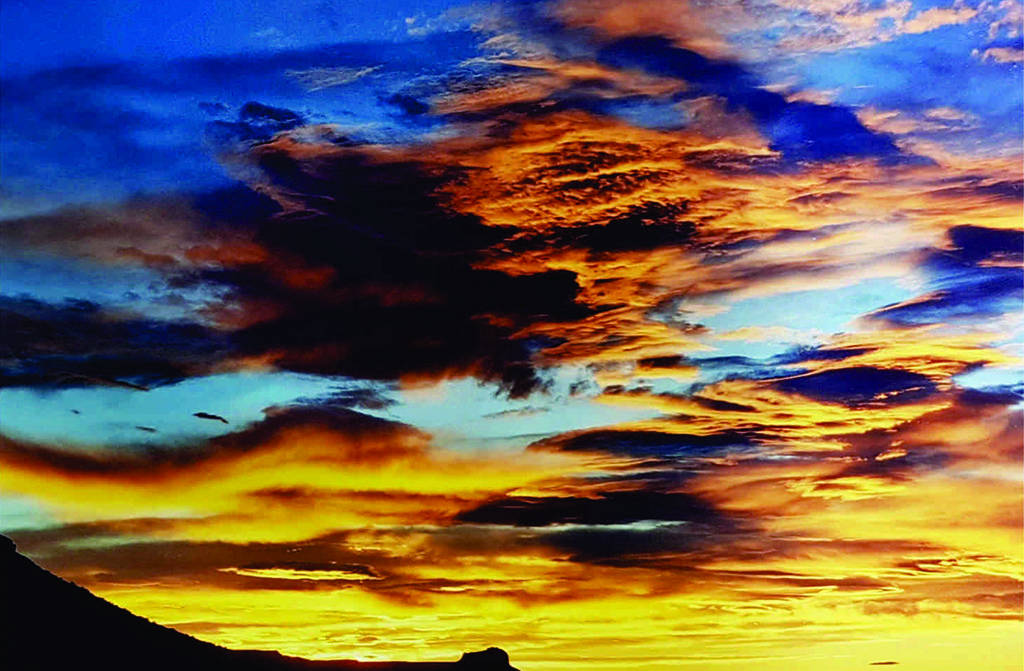

However, for me, it is enough to walk on a stony ground stripped by the wind or to stop at the foot of an ignimbrite wall, on an evening of tangential lights, to stir the imagination and recreate those extinguished worlds…

Figure 8. Ignimbrite walls shaped by erosion, under the unparalleled Patagonian sky.

Dr. Patricia Sruoga

CONICET Researcher

and SEGEMAR Geologist

Este conteúdo também está disponível em português | This content is also available in Spanish